16 July 2021

Dr Gary Foley is a founder of the Aboriginal Legal Service. To mark our 50th anniversary, we asked him to share his recollections of the racial justice movement in the 1970s and how the ALS began. Below is Part 2 of his essay, White Police and Black Power: The Origins of the Aboriginal Legal Service.

⫷Missed Part 1? Start at the beginning.

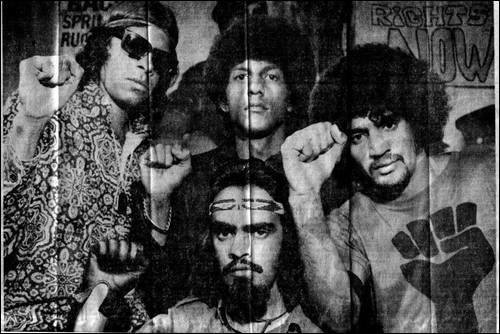

Gary Foley (foreground), an anonymous activist (left), Billy Craigie (right) and Denis Walker (centre).

The Australian Black Power movement

In 1973 on the occasion of Australia Day, Dr. Herbert Cole ("Nugget") Coombs, the Chairman of the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, Governor of the Reserve Bank and influential government advisor to six Australian Prime Ministers, speaking at a University of Western Australia Summer School, declared:

The emergence of what might be called an Aboriginal intelligentsia is taking place in Redfern and other urban centres. It is a politically active intelligentsia… I think they are the most interesting group to emerge from the political point of view in the whole of the Aboriginal community in Australia.

Coombs' belated realisation was already shared by many with an intimate knowledge of the Indigenous community of the day. What he was specifically referring to, but too timid to spell out, was a newly emerged collective of activists who would become known (among other things) as the Australian Black Power movement.

This group of activists in Redfern were closely aligned with similar collectives in Brisbane and Melbourne. They would develop a coherent ideology of which a central part was a concept they developed around community-controlled self-help organisations, consistent with their notions of self-determination.

It was from that scenario that the Aboriginal Legal Service had its origins.

Black Power was a political movement that emerged among African-Americans in the United States in the mid-1960s, seeking to express a new racial consciousness. Robert Williams of the NAACP was the first to put the actual term to effective use in the late 1950s.

Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael also had major roles in the formation of the ideas of Black Power. Malcolm X inspired a generation of Black activists throughout America and beyond, whilst Carmichael made Black Power more popular, largely through his use of the term while reorganising the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) so that white people would no longer possess leadership responsibilities.

The term was catapulted into the Australian imagination when the Victorian Aborigines Advancement League (AAL) invited a Caribbean activist and academic, Dr. Roosevelt Brown, to give a talk on Black Power in Melbourne in 1968. The AAL was led by Bruce McGuinness and Bob Maza, who were galvanised by the same notions as Malcolm and Stokely.

Bob Maza (right) with the former General Secretary of the Victorian Aborigines Advancement League in 1970.

The initial result was a frenzied media overreaction that was closely observed by younger activists in Brisbane and Sydney. Thus the term 'Black Power' came into use by a frustrated and impatient new Indigenous political generation.

For the purpose of this article I define the 'Black Power movement' as the loose coalition of individual young Indigenous activists who emerged in Redfern, Fitzroy and South Brisbane in the period immediately after Charles Perkins' Freedom Ride in 1965.

In this article I am particularly interested in the small group of individuals involved at the core of the Redfern Black Power movement, which existed under a variety of tags including the 'Black Caucus'. This group themselves defined the nature of the concept of Black Power that they espoused.

Roberta (then Bobbi) Sykes said Australian Black Power had its own interpretation, distinct from that used in the United States. She said it was about:

The power generated by people who seek to identify their own problems and those of the community as a whole, and who strive to take action in all possible forms to solve those problems.

In Redfern, Paul Coe saw it as the need for Aboriginal people to:

Take control both of the economical, the political and cultural resources of the people and of the land…so that they themselves have got the power to determine their own future.

Chicka Dixon and Paul Coe.

Bruce McGuinness, speaking in 1969 as Director of the Victorian AAL, declared that Black Power "does not necessarily involve violence" but rather was "in essence…that black people are more likely to achieve freedom and justice…by working together as a group".

So, the Australian version of Black Power, like its American counterpart, was essentially about the necessity for Black people to define the world in their own terms, and to seek self-determination and independence on their own terms, without white interference.

Maori academic Linda Tuhiwai Smith, in her book Decolonising Methodologies has asserted:

A critical aspect of the struggle for self-determination has involved questions relating to our history as indigenous peoples and a critique of how we, as the Other, have been represented or excluded from various accounts...indigenous groups have argued that history is important for understanding the present and that reclaiming history is a critical and essential aspect of decolonization.

Further, the great American historian Howard Zinn postulated that a national history serves only to justify the existence of the nation, which means, mainly, that it lies. If it ever tells the truth, it tells it too fast, racing past atrocity to dwell on glory.

Moments of importance and significance to Indigenous peoples are almost always drowned by the more powerful national narrative.

Thus, an Indigenous version of events from an Indigenous perspective is important for a greater understanding of where we have been and what lessons, if any, such an understanding might tell us about where we are today.